These days, diet choices are not just about nutrition or taste preferences. Diet choices come via social media influence, with a side dish of guilt and heaps of confusion. I’ve been doing a LOT of reading about varying nutritional advice – particularly the sorts that are used in marketing – and, I can’t make heads nor tails of it. What I can say, with confidence, is that there is not scientific consensus on what type of diet is “most healthy”. This is most likely because the “most healthy” diet for one person is not the “most healthy” diet for the next person. Plus, I’m not a nutritionist, so I wouldn’t dream of giving advice on what people should or shouldn’t eat.

For the purposes of this article, I am not looking at the health of the individual so much as the health of our environment. The environmental impact of our food choices is actually more straightforward in scientific research than health impact. Spoiler alert: while meat and dairy carry higher carbon footprints, the best thing you can do for the environment is not necessarily to go vegan. Eating less processed, more natural foods that are farmed responsibly will reduce the negative impact on the environment of your food choices.

This absolutely can include naturally raised (ideally organically farmed, or at least sustainably produced) livestock, fish and dairy products. Moving to less intensive production carries a cost, though. So, if your food budget is fixed, eating more sustainably could very well mean eating less meat so you can afford to eat smaller volumes of higher quality meat. This will have the added benefit of bringing down your carbon footprint by reducing your demand for high-emission meat products. You can also make the choice to avoid eating meat from restaurants or other sources when the origin of the meat is unclear. But, for heaven sakes, stop judging yourself (or others!) for what they do and don’t eat. There is so much ridiculous food marketing out there that it is virtually impossible to make a call on the “right” or “wrong” diet. No such thing exists. If someone tells you it does, try to find out what they are selling you.

Impact Based Decision Making

In making my food choices for daily meals at home and eating out or with friends, I try to consider multiple elements of environmental impact: carbon footprint, soil health, biodiversity, and welfare of humans and animals in the food supply chain. These factors are complex, and sometimes they offset each other. For example, high food yields result in high human welfare, as they can feed more people, but they often result in poor soil health and have a negative impact on biodiversity. This makes it difficult to have a single “right answer” when it comes to food choices. As with anything, there are positive impacts and negative impacts associated with every choice. My aim is to maximize the positive impacts and minimize the negative ones. But, before I explain my food choice decision tree, I will summarize the research that frames my methodology.

#1 Carbon footprint

Going fully vegan could reduce the carbon footprint associated with the food you consume by up to 73%. This is based on a small number of research papers, and requires validation. However, it is the best measure we have at this time. The carbon footprint associated with the food we eat makes up only 15-17% of the average carbon footprint of a household. So, if you reduce your food carbon footprint by 73%, you will impact your total carbon footprint by 10-12%. So, don’t stress if you cannot face the possibility of going vegan, or if a vegan diet is not the healthiest choice for you. There are lots of ways you can reduce your carbon footprint by 10-12%. These numbers are simply useful in helping us to understand the scale of impact we can have by changing the way we eat. They are certainly not meant to be proscriptive, and I am skeptical of those who use them in that way.

The carbon footprint linked to the food you eat has many elements. The type of food, the method of production, and the distance between food production and food consumption are all things that can impact the carbon footprint associated with the food you consume. By regularly choosing foods that have a lower carbon footprint, you can have a measurable impact on your carbon footprint.

The Environmental Working Group has put together a handy chart that shows you how different foods stack up against each other with regard to the carbon footprint associated with their production. Carbon emissions are highest amongst ruminant animals: beef and lamb, for example. Cattle beef by far has the highest estimated emissions associated with its production. Ruminant animals emit methane when they burp and toot, significantly increasing the emissions they produce in a lifetime. Methane has a warming capacity 80 times greater than CO2 in the 20 years after it enters the environment. However, methane does not stay in the environment as long as CO2, so there is the opportunity to have a greater impact in the “short”-term by reducing methane emissions. As well, there is encouraging research regarding the impact of adding seaweed to cattle feed, which holds the potential to reduce methane emissions in future (research on this is emerging). Chicken and responsibly farmed fish, on the other hand, emit one-tenth of the emissions associated with cattle beef, on average.

Taking these data on board, we can estimate that if one person switched two portions a week from beef to chicken, s/he would reduce his/her annual carbon emissions by about 4,575kg. If all the meat eaters on the planet did that, it would reduce carbon emissions by 30 billion tonnes each year.*

Other emissions associated the food supply chain that get a lot of focus are the transport miles between the farm and your local distribution center (as in, how far did your vegetables travel to get to the shop), and the miles between your house and the shop or distribution center. You can reduce the carbon footprint associated with your weekly shop by choosing produce that was grown closer to home. However, you can see from this World in Data chart that compared to food production itself, the carbon footprint associated with food transport is relatively small.

So, if you are deciding between beef farmed down the road or beans grown half-way around the world, the emissions associated with the beans will still be lower. That is not to say that beans grown half way around the world are always the appropriate choice – as certainly there are other factors to consider. It is safe to say, however, that locally grown beans have a much lower carbon footprint than beef. Therefore, swapping a beef stew for a bean stew every once in a while does make a difference in emissions.

#2 Farming methods

One benefit of eating less meat is that it frees up more budget for higher quality food items that are farmed less intensively. Intensive farming refers to farming practices that rely on large amounts of capital and labor inputs in order to maximize agricultural outputs across a land area. Intensive farming has been very successful over recent decades in increasing crop yields. This is typically done through increasing the use of pesticides and fertilizer. There are many benefits to intensive farming, which include higher crop yields, greater variation in the food we can grow, and lower food prices. However, there are a number of unintended consequences that the scientific community are only beginning to document, including poorer soil health, reduced biodiversity, and potentially a reduction in long-term yields.

There is a growing body of scientific evidence that connects intensive agricultural practice with negative environmental impacts, such as soil degradation, lower crop yields, and higher requirements for chemical interventions, like pesticides. There have been a number of anxiety inducing headlines stating that we only have 60-100 harvests left in the world’s soil. These headlines are exaggerated, as demonstrated by Our World in Data – Soil Lifespans. But, just because these claims are overblown, it doesn’t mean there isn’t any nugget of truth in them. 16% of soils are projected to have short remaining lifespans, and that is a significant number. The scientific community does agree that soil degradation is an issue that will impact yields in the future, if nothing is done. Improved agricultural practices can protect and improve soil conditions and therefore can protect future yields.

Organic farming relies primarily on natural methods of pest control and does not allow the use of chemical pesticides. On occasion, as a last resort, organic farmers can use a small set of naturally derived pesticides as a (like citronella and clove oil….and if you’ve ever used a citronella candle or arm band to ward off mosquitoes, you’ll appreciate the difference in these methods of pest control versus DEET). Organic farming reduces the amount of chemicals that enter the environment, and therefore does not negatively impact biodiversity in the way that chemical pesticides do. Organic farming methods result in better soil health over the long run and better populations of insects, birds and other wildlife with whom we share the land.

Organic practices also carry the highest standards of animal welfare. From living conditions and feed, to transportation and slaughter, organically produced meat provides the highest standards of the living and dying for animals in the food supply chain. If you are considering a vegan or vegetarian diet in order to improve the lives and deaths of livestock animals, that is a pretty straightforward decision.

Organic farming has lower direct emissions associated with agricultural inputs. However, research on the topic is nascent and so far has shown mixed results. The tricky bit comes with considering a shift to organic farming in context. Let me explain. According to the research available, it is reasonable to conclude that an individual farm could reduce its emissions by switching to organic farming methods. Organic farming requires fewer chemical inputs and fertilizers, all of which have emissions associated with them. Studies looking at less intensive farming practice, coupled with organic methods do show significant reductions in emissions. However, they also show much lower crop yields.

So, the scientific community cannot say, with confidence, that local switching to organic farming will result in global GHG emission reductions. You see, in order to maintain consumption levels, we would start importing more food to make up for the shortfall in domestic production caused by switching to less intensive organic farming methods. That imported food has higher emissions associated with it. So, when you consider a switch to organic farming in a global context in which consumption patterns remain the same, the results are mixed.

#3 Biodiversity Loss

There is an abundance of scientific literature documenting biodiversity decline: wildlife populations have fallen by an average of 69% between 1970 and 2018. Species are disappearing at 1,000 times the rate they did before humans existed, and at 10 times the rate deemed safe by the international scientific community.

Over 75% of global agricultural land is now used either as pasture for livestock or to raise feed crops for domestic and international livestock markets. More than 50% of the Amazon’s Cerrado, a woodland savanna ecosystem known for its rare species, has also been cleared for raising cattle and soy. There are a number of scientific papers linking historic deforestation to the rise in global meat consumption. According to a 2006 FAO report:

“Livestock are one of the major drivers of habitat change (deforestation, destruction of riparian forests, drainage of wetlands), be it for livestock production itself or for feed production. Livestock also directly contribute to habitat change as overgrazing and overstocking accelerate desertification.”

According to science.org: “substituting meat with soy protein could reduce total human biomass appropriation in 2050 by 94% below 2000 baseline levels and greatly reduce other environmental impacts related to use of water, fertilizer, fossil fuel, and biocides.” A number of follow up studies have been able to confirm or repeat similar findings. See the resources section below for more information.

The Sustainable Eating Decision Tree

I have a method for making food choices, both at home and when eating out, based on the various environmental impacts associated with various choices. Every person is different, and I’d encourage you to develop or adapt various methodologies to your own preferences and priorities. In our house, we’ve been flexitarian and full on meat eaters at different times (more on that later). Throughout our journey, I’ve developed my own balance of what and why I make the food choices I do. For me, it gives me the freedom to eat out and eat with friends, without any additional anxiety of whether I can stick to a strict diet, but still enables me to feel good about my food choices, knowing I am doing what I can to reduce the negative impact I have on the environment.

Eating with friends

The biggest challenge I encounter when attempting to stick to a vegan diet is eating with friends. I am not comfortable asking friends who are hosting our family to cater for a vegan diet. I completely understand why strict vegans do, and I have the utmost respect for those who can stick to a strict diet. I’m perfectly happy catering for vegan or vegetarian friends, and I feel a lot more comfortable doing so now that I have spent time learning how to cook vegan meals. But, most of my friends are not vegan, and because we are not strictly vegan in our house, it seems silly to expect that friends would cater for our “flexitarianism“. So, when a friend is kind enough to open his or her home to our family, I will eat whatever is served happily. It is a great way to give myself a break and indulge a bit. Taking this approach means, though, that I would not label myself as vegan or vegetarian. In social times, like the holiday period, I probably eat too much meat, too many carbs, and not enough vegetables. But, life is short, and I’m too old to worry about these sorts of things. I fear the anxiety associated with worrying about it would undo any health benefit a strict diet would bring!

Eating out

When we eat out as a family, we are more likely to choose restaurants with vegan and vegetarian options. It has been amazing to watch the evolution of restaurant service in recent years – even a number of our local pubs now offer vegan and vegetarian meals on a regular basis. As well, there are many more options for getting a healthy, vegetable focused meal at a new offering of cafes and high-end restaurants. And, of course, in London, the vegan and vegetarian trends are incredibly well catered for.

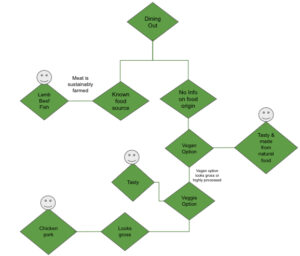

That being said, when dining with friends, or trying out a new place, options can sometimes be limited. And, offering a vegan or vegetarian option isn’t enough – it still has to taste good. Some pubs and restaurants that are new to the vegetarian and vegan game still have some kinks to work out in the flavor department. So I have a philosophy I apply when choosing my meal. It looks sort of like this:

#1 – If there is information about the source of ingredients, I will eat whatever I feel like. If there is organic or sustainably farmed beef, lamb, pork, chicken or fish, I will choose that. But, if there is no information about how food is sourced, I will look for non-meat options. If there is a vegan option that sounds appealing, I will choose that. My reasoning for this is that this option is likely to have the lowest carbon footprint of all options on the menu, due to the lack of meat and dairy. It also encourages restaurants to provide more vegan options in future by boosting the demand for vegan food. The higher the supply of vegan options, the more varied and competitive the offerings will become, putting pressure on restaurants to make more of them and to make them delicious. I will not choose the vegan option if it is highly processed (like fake vegan chicken wings, or vegan sausages). Processed foods carry high carbon footprints. Eating real, sustainably farmed chicken or pork probably has an equal or lower carbon footprint than a manufactured fake sausage.

#2 – If the vegan option(s) are not appealing, I will then look for an appealing vegetarian option. My rationale is the same as for option #1, knowing that the introduction of dairy into the meal will still likely have a lower carbon footprint than meals containing meat.

#3 – If there are no appealing vegan or vegetarian options, I will choose the right dish for me based on a combination of which dishes look appealing, and what I know about the meat in them. A lot of the pubs near us source meat locally – and if the meat is coming from a sustainable local farm, I’m more likely to choose it, even if it is the type of meat that has a higher carbon footprint, like beef or lamb. 99% of lamb is produced in extensive farming systems, for example, so it is less likely to have other deleterious impacts on the environment (apart from the emissions associated with the animals themselves). If the source of the meat is unknown, I will likely choose chicken or pork, as these have lower carbon footprints than beef and lamb. Fish is tricky; there are many types of fish and many methods for sustainable and unsustainable fish production. I tend to not order fish unless I am near the source and the fish is fresh and sustainably farmed or caught.

Eating at home

My home environment is where I have the greatest control over what I eat. During the week, if I’m eating at home, I will cook vegan meals most of the time for myself and my partner. This can be difficult (or at least mildly annoying) because I have kids and my kids are not vegan. They will eat a lot of vegetarian and vegan meals, but not all of them.

Weirdly they love tofu. Like, really love it – I find it hilarious how much they love tofu given how passionate so many adults are about hating it. So, with the kids, I cook them sustainably produced meat and fish as well as vegetarian and vegan dishes. These days, I am buying less meet for a family of four than I used to buy for just my partner and myself before our our diet change. One of the great benefits of that is that by spending less on meat, I can put the same budget towards higher quality meat, with greater animal welfare and a reduced impact on the environment.

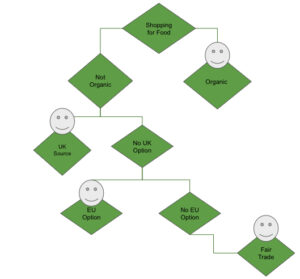

When it comes to fruit and veg, I rely on my weekly organic vegetable box delivery for most fruit and vegetables we consume. I’ve chosen this option as it ensures my food was produced using sustainable farming methods and has zero air freight miles associated with getting to my door. At the supermarket, I choose organic when that is possible. When it is not, I choose produce from the United Kingdom, as the UK has relatively high standards for food production and relatively sound restrictions on pesticide use (though, they could be stronger in my opinion). If the food was farmed in the UK, it is also has fewer transportation miles. If I cannot find what I need produced organically or in the UK, I look for an EU option. The EU also has high standards for pesticide restrictions and is the next best option for reducing food travel miles to the UK.

Conclusion

It is ok to write your own rules for making sustainable food choices. It is ok to have a different definition of vegan or vegetarian that suits your priorities and principles. Every sustainability choice helps. Every time you choose to eat a vegetarian or vegan meal instead of a meat based meal, that makes a difference to the global demand for meat and your carbon footprint. Every time you can afford to buy organic beef over imported, intensively farmed beef, that makes a difference. It’s not about being perfect; it’s just about making minor changes over a prolonged period of time.

I aim for optimized choices, in which sustainability of food choice is considered across as many of these elements as is possible. But, I recognize that there are always compromises in complex decision making, so I do the best I can. I don’t pretend that my decision making framework is perfect, and I don’t pretend to always stick to it. I have days when I make poor food choices. I just try to remember that every little helps – every choice I make with sustainability in mind is a positive thing. Overall, thinking about my food choices is better than not considering them at all, even if my choices aren’t always perfect.

Resources

Science Direct: Agricultural Specialization

Impacts of dietary change on greenhouse gas emissions

Conserve Energy: Intensive Farming

Organic Farming & Crop Rotation

Meat eating impact on biodiversity (news article on study release)

Guardian Article on Biodiversity