What you need to know:

- Strict vegans do not eat honey as it is an animal product.

- While data are insufficient to draw detailed global conclusions about bee populations across species and countries, existing evidence suggests that pollinator populations are declining dramatically.

- Lack of natural pollinators is already having a negative impact on food crop yields and input costs for farmers, who in some cases are resorting to human pollination.

- Honeybee populations, on the other hand, have been growing in many countries, and the demand for honey as a food crop is a significant contributor to this trend.

One of the new learnings for me during my foray into vegan(ish) living was that honey is off the menu for strict vegans. When I spent a few seconds thinking about it, of course, I realized that honey is an animal product and therefore not strictly vegan. I guess I hadn’t really thought about honeybees as livestock before.

But, it raised an interesting question in my mind. What is better for the environment, eating honey or not eating honey? I pursued a vegan diet out of a desire to reduce my carbon footprint, not out of a desire to stop the exploitation of animals that provide us with food. We have a number of beehives on the family farm, and certainly from what I’ve seen there, the cultivation of bees is a positive way to ensure and grow the existence of much needed pollinators who are dying off in alarming numbers.

However, the vegan society recommends eliminating honey from your diet because honey is the food source for bees, and without it they would starve. This argument does not line up with my experience of responsible beekeepers. Just like chickens, cows, pigs and sheep would starve should farmers not feed them, cultivated honey bees typically make more than enough honey to feed themselves and provide surplus for farmers.

In winters when not enough honey is produced, farmers feed their bees, just like livestock farmers feed their cows and sheep in winter. So, eating farmed honey does not result in bee starvation – quite the opposite. Eating farmed honey ensures there are a multitude of cultivated bees who are cared for by responsible farmers.

Let’s address this first accusation: that beekeepers take all of the honey and feed bees sugar syrup instead. That may be true of some irresponsible beekeepers, but it wouldn’t be a very long lasting farming practice. Most beekeepers I know are very interested in the health and wellbeing of their bees. Because honey production relies on healthy live bees, it is in the interest of the beekeeper to provide well for his or her bees. So, let’s separate responsible beekeepers from irresponsible ones.

Responsible beekeepers leave enough honey for the bees to stay well fed through winter, and harvest honey from the other frames in the hive. Sometimes they get the amounts wrong, though, and do need to feed the bees in order to keep them strong and healthy enough to make it to the spring nectar flow. So, the argument that eating honey is unethical because the bees are fed unhealthy sugar syrup or left to starve is not true if you buy honey from a responsible beekeeper.

The vegan society goes on to describe harmful cultivation practices – like clipping the wings of Queen bees to prevent them leaving the hives. I have little doubt there are bad actors that keep bees with short-term gain only in mind, and that operate irresponsibly and in ways that cause damage to the hive. As with many types of cultivation or farming, there are responsible practices and irresponsible practices. The key takeaway is that if you are happy to eat honey as an animal product, but you want to ensure that your food choice is as sustainable and ethical as possible, it is important that you source your honey from responsible beekeepers.

I believe that most beekeepers are responsible and want the best for their bees. This is most likely my experience because I’m interacting with smallholding beekeepers, who are more “farmer” and less “industry”. The most egregious references to poor beekeeping practices are associated with large scale industrial farming. So, if you can buy local honey from a responsible farm, do that. If you do not have local producers in your area, it is worth paying more for organically farmed honey, which will carry with it more responsible agricultural practice and therefore reduce the risk of bad practices in bee cultivation.

Economically speaking, the logic holds that by consuming responsibly farmed honey, we are stimulating the supply of responsibly farmed hone, which will help to ensure a robust market of bee cultivation, which will help bee populations to remain strong over time. And, in fact, this is what long term data tells us.

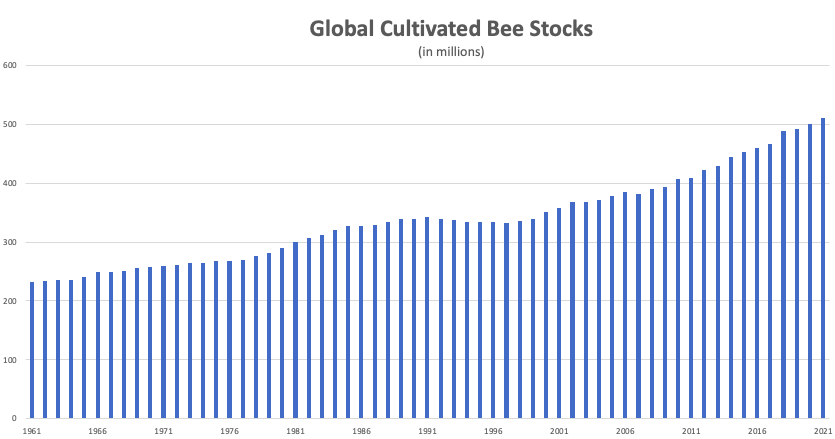

Honey consumption has been rising globally, and in the US hit an all time high in 2021. To satisfy the increasing demand for honey, global stocks of honeybees have been rising as well. Even with difficulties in recent years caused by Colony Collapse Disorder in the US, the number of honeybee hives has grown since 1969 – from 1.42 million to 2.88 million in 2017. According to FAOSTAT, the statistical arm of the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), global cultivated bee stocks have been rising steadily across the globe since the 1960s.

Source: FAOSTAT

Even if we didn’t eat honey, domesticated bees would continue to be cultivated, as many bees are cultivated for the purposes not only of harvesting honey, but also to serve as pollinators in intensive agricultural practice. Intensive agriculture practice, the kind where you grow one crop across lots and lots of acres or hectares, eliminates the hedgerows and wildflower meadows where wild bees would typically nest. So, by removing the natural habitat, farmers in intensive systems then have to reintroduce bees to pollinate their crops. This is often accomplished by renting bees from nearby beekeepers.

So, what is the right answer? Well, as with most complex issues, there is no simple right or wrong, only opposing forces with different consequences. On the one hand, beekeeping associations and local beekeepers are incredibly important for keeping honey bee populations strong.

Cultivated bees are one of the few pollinator types that are demonstrating global growth (of course full comparison is limited by lack of data). In my experience, eating honey is a personal choice, and those who are vegan out of a desire to protect animals of all kinds from any exploitation through cultivation are significantly more likely to opt for maple or date syrup instead of honey. Vegans who are vegan either for health or sustainability reasons are more likely to consume honey.

Whether or not consumption of honey has a positive impact on overall pollinator ecosystems cannot be determined with available data. However, we can conclude that consumption of honey and the use of cultivated bees in agricultural pollination are keeping honey bee populations rising in a world where evidence suggests most pollinator species are under growing pressure to keep populations stable or grow.

For more insights on what it is like to keep bees, check out this video. If you are more interested in the key facts and figures regarding pollinator population declines and how our food chains depend on them, keep reading.

What is happening to bee populations?

Bee populations, and indeed the populations of all types of pollinators, including butterflies, birds and other insects, are declining worldwide, according to scientific consensus. According to the FAO:

“Bees and other pollinators are declining in abundance in many parts of the world largely due to intensive farming practices, mono-cropping, excessive use of agricultural chemicals and higher temperatures associated with climate change, affecting not only crop yields but also nutrition.”

This conclusion, that pollinator populations are declining, is abundant in the headlines, but the underlying data on which it is based is sparse and local. According to a recent Assessment report on Pollinators, Pollination, and Food Production by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES):

“Wild pollinators have declined in occurrence and diversity (and abundance for certain species) at local and regional scales in North West Europe and North America. Although a lack of wild pollinator data (species identity, distribution and abundance) for Latin America, Africa, Asia and Oceania preclude any general statement on their regional status, local declines have been recorded. Long-term international or national monitoring of both pollinators and pollination is urgently required to provide information on status and trends for most species and most parts of the world.”

So, from what I can tell, the scientific community is confident that global pollinator populations are declining, because nearly all of the local studies being carried out show declines in wild populations. For example, in the UK, a third of wild bees and hoverflies populations are in decline. The UK is monitoring 216 species of bee, and found that populations declined in 70% of these from 1980-2010. A flying biomass study carried out in Germany found that flying insects declined by 76-82% (depending on the season) between 1989 and 2016. 9% of bee and butterfly species in Europe are currently threatened, and populations are declining in 37% of bee species that are currently monitored. Unmonitored species make up 57% of bee species, so that 37% figure is only representing less than half of bee species overall.

There is general consensus that populations of all pollinators are falling overall worldwide, and emerging research is reinforcing these conclusions. However, time series data (data points that can track trends over time) on bee populations globally are not available. So, we cannot say with much confidence by how much wild bee populations are changing. What we can say is that more scientific study is required in this area.

The most widely available data come from monitoring of cultivated bees only, giving very little insight into how wild bee populations are doing.

Data from FAO’s statistical database, FAOSTAT, demonstrate that the number of managed western honey-bee hives has been increasing globally over the last several decades. In 1961, countries reported fewer than 50 million hives. In 2016, they reported more than 90.5 million hives, producing nearly 1.8 million tonnes of honey annually. IPBES (2016a), however, notes that, despite the overall upward trends globally, important seasonal colony losses are known to occur in some European countries and in North America (data for other regions of the world are largely lacking). For example, in the US, there have been serious colony losses as a result of pests and pathogens in addition to habitat loss and the use of pesticides. Responders to this FAO report stated unequivocally that pollinator populations are declining in grassland based livestock farming systems. However, populations of pollinators are stable or showing mixed results across other farming systems.

In summary, there is evidence that the diversity of bee species is declining, and overall bee populations are showing mixed results: some populations are increasing, some are declining, and some are stable. Despite losing many types of bees, some of the species that remain are thriving, for example. And if they are growing by a larger volume than the species have lost, then overall populations could be rising in some geographic regions. So, for that reason, when activists call out for action, they typically refer to the figures related to species loss, rather than population changes.

Before you get too optimistic, though, it is worth noting that globally, the scientific community accepts that pollinator populations are declining at an alarming rate. The challenge with bees is that there is a mix of wild and domesticated bees, and since domesticated bees have economic value (honey and pollination services to intensive agriculture systems), they are faring pretty well across the globe. So, this takes us back to our question: is eating honey good for the environment? Overall, it is hard to say, but what we can say with relative confidence is that eating responsibly farmed honey does have a positive impact on cultivated bee populations.

Why do we need bees and other pollinators?

Overall, pollinators support between $235 and $577 billion of annual food production globally. Of the more than 100 crop species that provide 90 percent of food supplies for 146 countries, over 70% are pollinated by bees, and several others are pollinated by thrips, wasps, flies, beetles, moths and other insects. In Europe alone, 84% of the 264 crop species are animal-pollinated and 4 000 vegetable species have their life assured thanks to the pollination of the bees.

That being said, while nearly 75% of our crops depend on pollinators to some extent, only 35% of global crop production does. That is because many of our staple foods (the ones of which we eat a lot – like cereals) are not dependent on pollinators at all. They are wind-pollinated.

Crop yields also have a positive relationship with diverse and robust pollinator populations, meaning that natural pollinators help improve crop yields, even when they are not directly involved in the actual pollination. According to the FAO, “higher pollinator density and higher species diversity of pollinator visits to flowers have been found to be associated with higher crop yields”.

It is common for farmers in intensive farming practice to rent honeybees in order to have a large enough population of pollinators to pollinate large crop acreages, and to offset the loss of nearby natural habitats of pollinators that exist in traditional, ecological farming practices – like hedgerows.

So, while we may not see a widespread food shortage as a result of pollinator decline, many popular food crops depend on pollinators, like bees, and will suffer reduced yields as pollinator populations continue to decline. According to our world in data, crop production would decline by around 5% in higher income countries, and by about 8% in lower/middle income countries if pollinator insects vanish.

If we do not revive the populations of our pollinators, we will have to rely more and more on other methods of pollinating the crops that end up as food on our tables. Hand pollination is already seen across 20 crops, including vanilla, passion fruit, date palm, oil palm, cocoa, and specific species of apples. Hand pollination can reduce financial losses associated with a lack of natural pollinators, but it is certainly not the most efficient way to cultivate these crops. In 2020, a comprehensive study from Rutgers University stated that crop yields for apples, cherries and blueberries in the United States are already being impacted by reductions in available pollinators.

Overall, while the percentage (5-8%) of crop production impacted may not be that high in percentage terms, it represents a large volume of some of the most nutrient rich foods we consume. And, it is worth remembering that other impacts of pollinator loss are significant – reduced biodiversity will likely kick off negative feedback loops in the ecosystems that depend on them, causing a number of as yet unrealized consequences.

Pollinator Decline: Implications for Food Security & Environment